“Our linear minds do not like nuances and reduce the information to the binary “harmful” or “helpful.”

Nassim Taleb

“But to say the record of their transactions, the price chart, can be described by random processes is not to say the chart is irrational or haphazard; rather, it is to say it is unpredictable.”

Benoit Mandelbrot

“The returns from equity investing are quite risky. As a result, if the high average stock return of the past is the true long-term expected return, the high volatility of stock returns nevertheless means that getting a positive equity premium (of any size) is highly likely only for holding periods of 35 years (an investment lifetime) or more.”

Gene Fama

I want to give a gentle reminder that risk is always ever present in the financial markets (and in life itself). I have received many comments recently that investors want to get back “all in” because the markets are making a run. I am not against that if one understands the risks associated with that position. There is no free lunch.

Risk can be defined in different ways. One way in the investing world is called “standard deviation,” which is a fancy way of saying how much returns vary around the average over a given period.

Risk of ruin or major capital loss at the wrong time is another way to view risk. If one retires and loses half the value of their portfolio, which happened between late 2007 and early 2009 if one were invested 100% in US stocks, one’s retirement could be truly ruined. Having to withdraw from that nest egg after it was cut in half could pose real long-term financial independence problems. In financial planning terms, this is called “sequencing” risk, which is having a major loss at the same time you need to draw from your portfolio.

As famed mathematician and investor Ed Thorp wrote in his autobiography, “understanding and dealing correctly with the trade-off between risk and return is a fundamental, but poorly understood, challenge faced by all gamblers and investors…People mostly don’t understand risk, reward and uncertainty.”

Thorp continues:

“Academic finance, as has been recently shown by Ole Peters and Murray Gell-Mann, did not get the point that avoiding ruin, as a general principle, makes your gambling and investment strategy extremely different from the one that is proposed by the academic literature.”

Why is risk so hard to understand in financial markets? One reason is people assume there are simple, linear, straight line explanations for market movements, which is untrue. Markets are complex systems, where the total is greater than the sum of its parts. In other words, the collective behavior of their parts entails the emergence of properties that can hardly, if not at all, be inferred from the properties of the parts. Ed Thorp says that “people tend to make the error of seeing patterns or explanations when there aren’t any, as we’ve seen from the history of gambling systems.”

Therefore, it is very hard to predict the impact of any one thing on a complex system. There is much uncertainty. For example, when governments and other quasi-governmental institutions like the Federal Reserve participate in unfamiliar ways in markets, such as huge monetary stimulus and bond buying that occurred in March and April and continues today, an argument can be made that normal market forces are being impacted by “non-market” players.

Some people do not think Federal Government intervention has much impact, although others are not so sure. Joe Norman, PhD, and principal of Applied Complexity Science, LLC and a complexity science expert, states that “money and prices are information, that when you add to supply you may ‘patch’ some shortfall in the near term, but also dilute information that is conveyed in transactions and prices. One may eventually cross a threshold where there’s not enough information for the system to hang together.”

Accurate prices are important for the correct allocation of resources. Manipulation of prices, whether by anti-competitive behavior of private market participants or government manipulation through abnormal Federal Reserve practices, can distort prices and information that would be contained in otherwise “market” prices.

Changes in market prices can occur very quickly and in large magnitude, just like this February and March. These are called “fat tail” events, and they occur more frequently than you would expect based upon on normal statistics. Nassim Taleb defines a fat tail as an “extreme event at a low frequency.”

Gene Fama wrote about fat tails in his dissertation in 1964.

“Half of my 1964 Ph.D. thesis is tests of market efficiency, and the other half is a detailed examination of the distribution of stock returns. Mandelbrot is right. The distribution is fat-tailed relative to the normal distribution. In other words, extreme returns occur much more often than would be expected if returns were normal.”

Benoit Mandelbrot goes on to say about markets that “the market is very risky—far more risky than if you blithely assume that prices meander around a polite Gaussian (normal distribution) average.” He states that the capacity for large “jumps, or discontinuity, is the principal conceptual difference between economics and classical physics.” He analogized that big floods “were like big price jumps; the disastrous droughts were market crashes.” And Nassim Taleb states that “financial matters – and other economic matters – tend to be from Extremistan, just like history, which moves by discontinuities and jumps from one state to another.”

As Mandelbrot continues:

“Unlike a broker, most investors do not care about ‘average’ returns. For them, the rare, out-of-average catastrophes loom larger… The ultimate fear is financial ruin.”

What risks exist in the marketplace today? Some are known, and many are unknown. Below are some risks:

- Domestic Political Risk

- Market or Pricing Risk

- Macroeconomic risk, such as unemployment, demand, etc.

- Default Risk of outstanding debt, both corporate, muni and other government debt

- Interest Rate Risk, related to the above

- Inflation Risk

- Proper functioning of treasury/credit markets, which stopped functioning normally in March

- Climate/Natural environment risk (hurricanes, flooding, etc.)

- Geopolitical Risk, including war

- Free trade risk

- Regarding the pandemic, vaccine, and shutdown risks

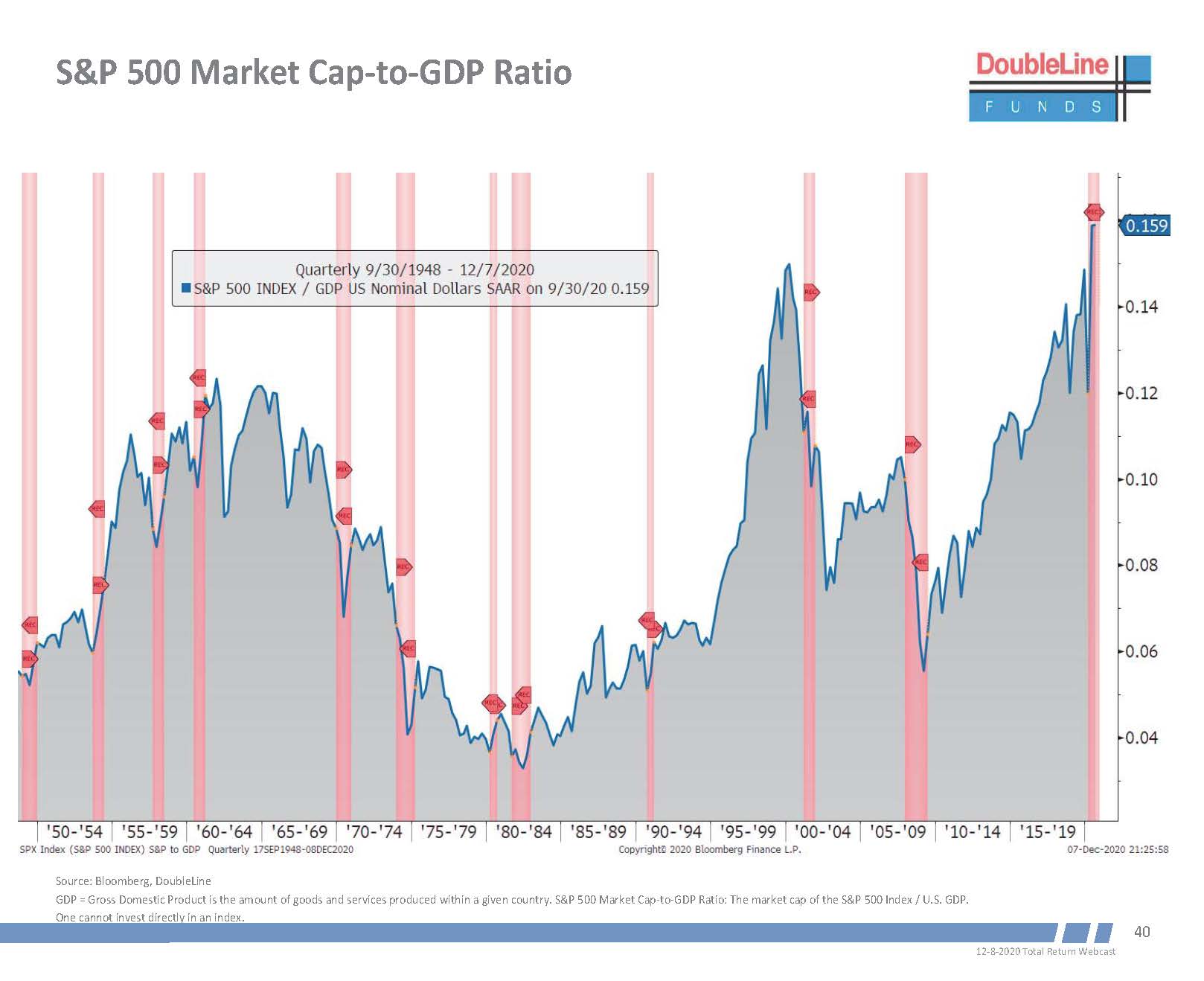

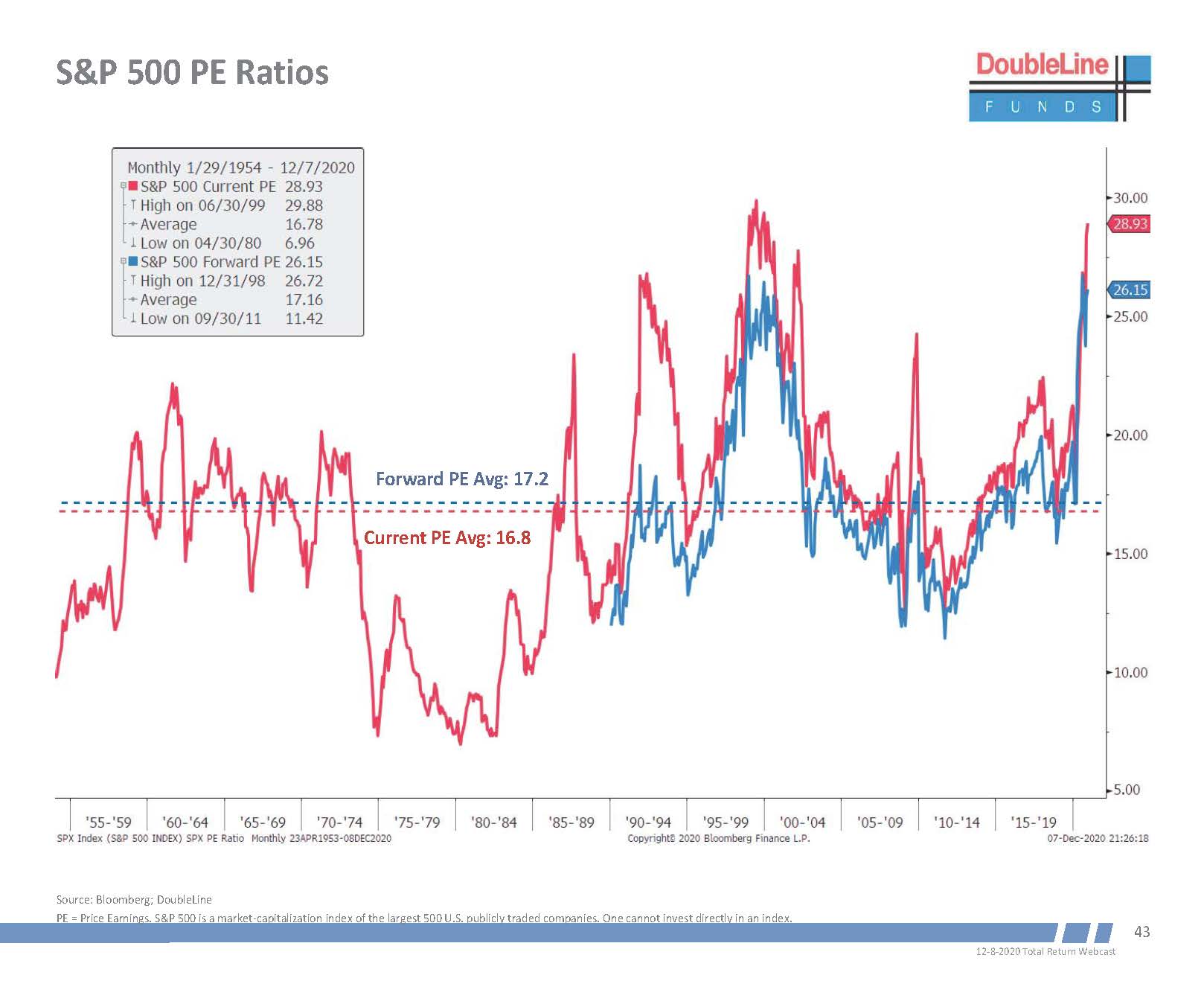

Expected returns in the markets are always positive, but they vary over time. Since markets are at high valuations, as shown by the graphs below, expected returns are lower than when the market is at lower valuations. One needs to consider their time horizon and cash needs when deciding on how much risk to take.

One can see that the market value is at an elevated level both as compared to the Gross Domestic Product of the United States (which is a favorite valuation metric of Warren Buffett) and compared to earnings.

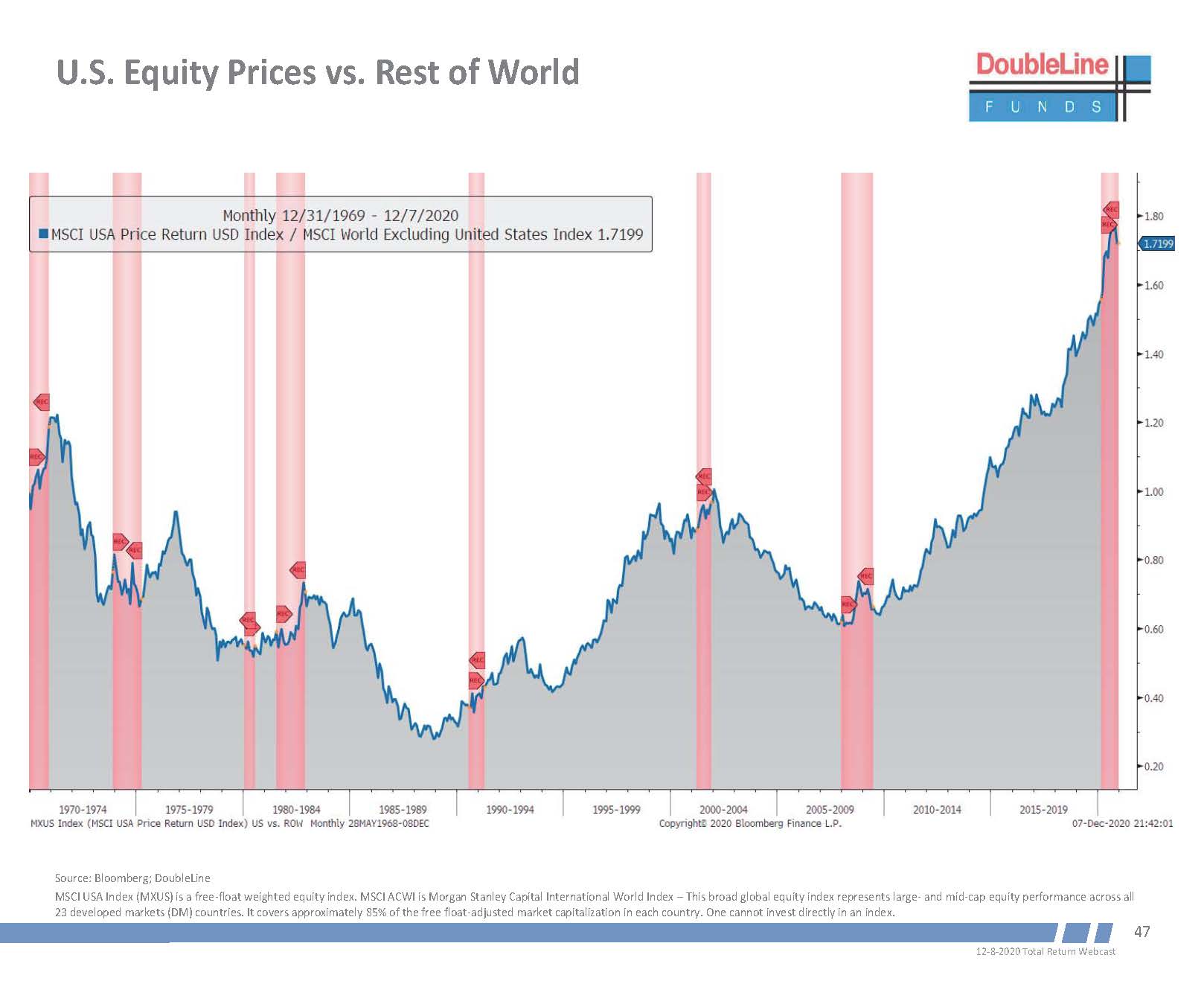

As you can see below, US stocks are priced high compared to international stocks.

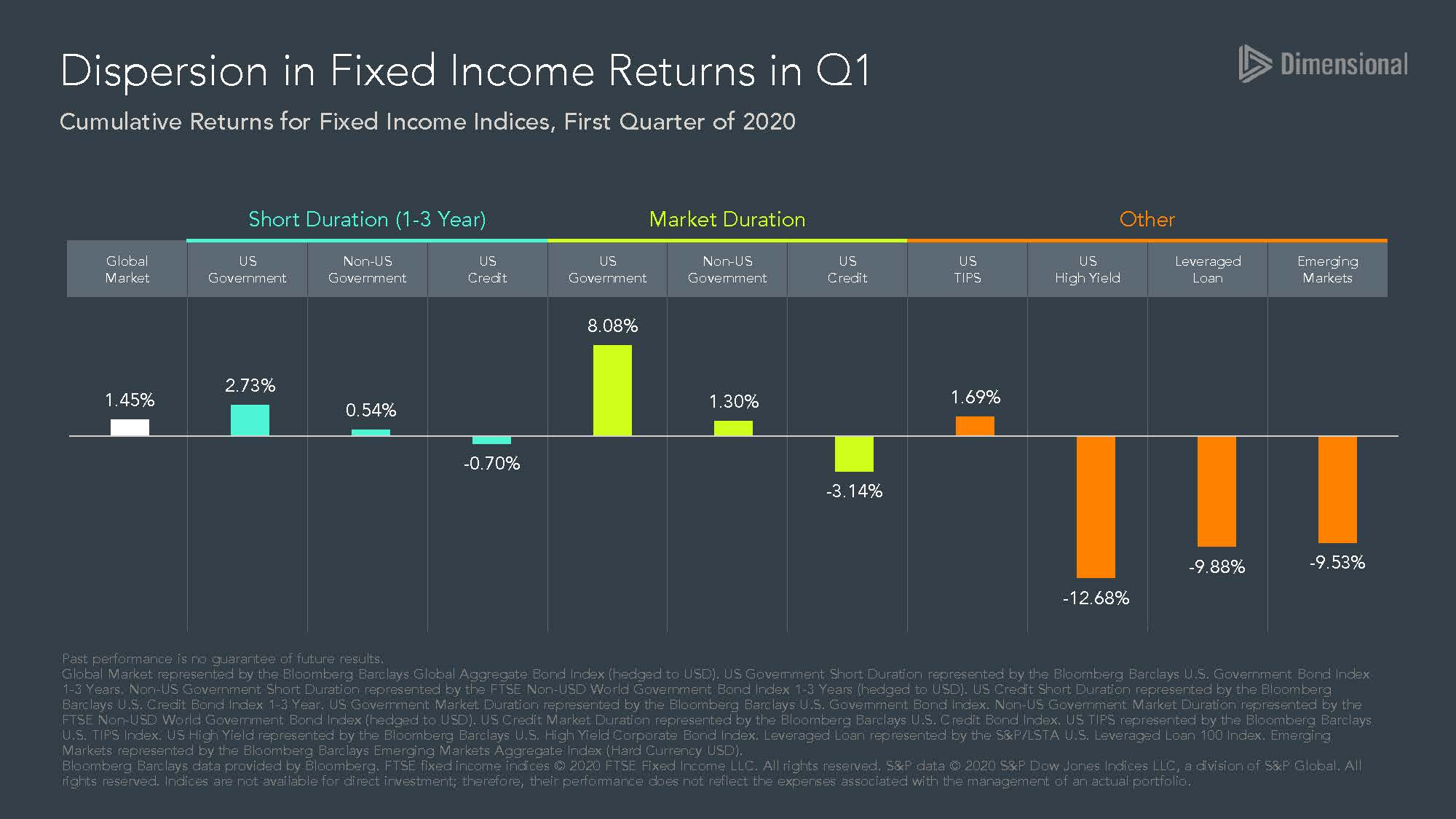

How does one protect against risk? The most important is to diversify across asset classes. Besides diversifying in stocks around the world and other “factors,” we believe shorter to intermediate bonds, including short-term US government debt, protects portfolios when uncertainty increases. Please look at the chart below on how different bond classes performed in February and March when stocks tanked. As you can see, US Government bonds did very well in an uncertain environment. High yield/junk did not, because that is risky debt, and that acts more like stocks.

There are other “tail” risk hedges that might make sense. We are reviewing a new low-cost ETF that we may implement into the portfolios that could provide some diversification that “insures” against risk by buying deep out of the money puts. Research shows that if implemented correctly, risk protection kicks in. Other things to focus on are low fees and expenses, and not trying to time the markets.

Passive investing is also a wise strategy. As Nobel prize winner Danny Kahneman wrote in Thinking Fast and Slow:

“The evidence from more than fifty years of research is conclusive: for a large majority of fund managers, the selection of stocks is more like rolling dice than like playing poker. Typically, at least two out of every three mutual funds underperform the overall market in any given year.”

And remember, those mutual fund managers are professional investors. The stats get worse over longer period of times. For example, 77.97% of Large Cap funds underperformed the S&P 500 over the past 5 years. See SPIVA (spindices.com).

Risk is always with us. As Mandelbrot found, “at short time frames prices vary wildly, and at longer time frames they start to settle down.” It is important to consider risk when investing. We are here to help you think through those issues when putting together your portfolio.

All the best,

Mike and Emily

P.S. I have been drafting this for several weeks. However, I dedicate this to my brother Jim, who passed away on Monday. Unfortunately, he was not able to overcome the risk of kidney disease. We will remember his kindness and smile throughout the holiday season and beyond. Rest in peace brother.